America is justly proud of its written Constitution.

Inspirational. At times brilliant. Yet notably imperfect.

The measure of a great society is how it deals with its flaws.

America is an “indirect” democracy. Citizens elect representatives to govern on their behalf, as part of a great Federation of far-flung states. In turn, those representatives swear to uphold a structure dividing the responsibilities of nationhood among two legislative houses, fifty states, a President, a Judicial court, and the natural rights of the people.

Despite this hierarchal, bureaucratic arrangement, the Constitution was conceived of as a living document, ultimately answerable to its citizens.

From the Nation’s very inception, we heeded that call. Voters linked ratifying the draft Constitution to the simultaneous introduction of the Bill of Rights.

But how can such a complex enterprise- a child of compromise just 8000 words long- remain a true servant of the People?

Chief among the Constitution’s many checks and balances on delegated power are semi-annual elections and the threat of impeachment proceedings. In principle, these strictures ensure our representatives are held accountable for their actions.

Annually updated laws and executive branch regulations are another adaptation to the passage of time. As society evolves, so must the law reflect the prevailing views and norms of the people.

But conflicts will arise. The Supreme Court steps in when laws are inconsistent with the Constitution, at odds with legal precedent, or simply reflects the inherent limitations of the written word and human experience.

This provision is made in a constitution intended to endure for ages to come, and, consequently, to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs.

Chief Justice Marshall, in McCulloch v Maryland 1819

But sometimes the day-to-day operation of the government becomes incommensurate with the times. Sometimes the legislators no longer listen to the people. Sometimes the rules themselves must be revisited.

By amending the very Constitution itself.

Each of the twenty seven amendments to the US Constitution followed a unique path to ratification. The first ten at our country’s birth mirrored the unresolved tensions between Federal and State, North and South, the government and the inherent natural rights of all people. The next seventeen appeared over the course of two centuries, generally in response to a crisis (like slavery and the civil war or an assassination). These amendments followed the Article V process, where they are first introduced in Congress, and when approved by a super-majority, are transferred to the states for ratification by another super-majority.

Slow, ponderous and careful. Perhaps reflecting the seriousness of the enterprise.

Every year, hundreds of amendments are introduced in Congress as part of the Article V process. Most are stunts- pandering to their representative’s base. Others are impractical, or frankly hair-brained. A few deserve our support. Yet, without the pressures of a crisis they languish. Waiting for a trigger to mobilize the body politic.

Isn’t there a better way?

All amendments are not equally important. On occasion, amendments like the 18th on Prohibition were a hurried response to the intersecting social concerns of temperance, women’s rights and immigration, and only survived 14 years.

Not every issue requires, or is even best served, by a constitutional amendment. In most cases, laws and regulations perform a satisfactory job of keeping the whole legal enterprise in sync with the times, albeit slowly and unevenly.

For example, the 27th Amendment (preventing Senators and Representatives from giving themselves a raise without an intervening election) in principle could have been rendered moot by a simple House and Senate rule.

“Gay marriage” could have been enshrined as a separate constitution amendment (or perhaps as part of a larger, more expansive definition of “inalienable” individual rights or a revised ERA). Instead, the Supreme Court agreed (after 30 years of citizen agitation and victories at the state and local levels) to discover a “new right” within the umbrella of the existing Constitution. A de facto decision made after society had moved on.

On the other hand, pent-up forces, like the inevitable rise of women as equal partners with men, were belatedly addressed by the 19th Amendment. Evening out the playing field, in a way only an amendment could rectify.

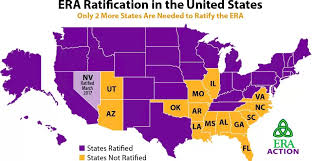

A seeming victory for women, but the unfinished business of sexual equality foundered on the inability of the co-pending Equal Rights Amendment to achieve ratification.

Words matter, and these amendments are often sloppily phrased or conceived. Endless Supreme Court arguments hinge on the meaning of phrases like “all people”, “jurisdiction” and “equal”. The placement of an errant comma can shift the rights of millions.

And who is to “guard the guards”? When our representative’s vested benefits are high (such as with gerrymandering protecting their seat or unseemly loyalty to their party over their constituents), they are unlikely to vote against their own self-interests.

Can’t we do better?

Article V offers a second path via a Constitutional Convention consisting of state delegates, elected by the people, who can directly amend the Constitution. Unfortunately, the Founding Fathers neglected to provide any binding rules for such a convention, leaving open the possibility it could spin out of control, radically and suddenly reframing our entire way of life. Perhaps under the control of a small number of delegates.

A public initiative, common in many states, is an alternative to a free-for-all at a convention. Such an initiative (which at the Federal level would require a Constitutional Amendment for implementation) short-circuits the Article V process. Directly expressing the will of the people. And it’s often been successful, forcing state legislatures to approve highly popular independent redistricting committees, or to tighten on-line privacy rules.

But a national initiative would be cumbersome- inevitably requiring a majority of people in a super-majority of states to approve the ballot issue for consideration, and then return to the electorate a second time for voting. Plus the history of state and local initiatives is a mixed bag- with wise legislation often outnumber by special interests.

WeAmend seeks a middle path. Avoiding the dangers of national referenda and conventions. Yet placing citizens directly in charge of selecting, crafting and navigating amendment through Congress and the States.

Amendments are debated in a public forum, outside of Congress.

Crowd-sourcing evolves the wording of each amendment, improving clarity and providing a documented history of intent.

A short list of widely support amendments emerge. A second Bill of Rights.

WeAmend works with Congress to smoothly approve amendments and send to states.

WeAmend works with state legislators and local organizations to swiftly ratify under the existing Article V process.

Seek stability. Embrace change.

Read more about the National Citizen’s Convention here.