We broke it, we own it

How to mend the constitution with a new crowd-sourced Bill of Rights

Benjamin Franklin, in response to a question from the engaging Mrs. Powel¹, reportedly quipped after the 1787 Constitutional Convention:

“Doctor, what have we got? A republic or a monarchy?”

To which Franklin supposedly cautioned: “A republic, if you can keep it.”

Which raises the obvious question: Is the Constitution, and by extension our democratic republic, a “keeper” or a “keepsake”? That is, should we view the Constitution as a sacred, immutable text handed down from a gloried past? A beacon of constancy in a changing and threatening world?

Or, must the Constitution mirror the current aspirations of the people, and like any reflection, shift and travel alongside the viewer? A document for which we are its “brother’s keeper”- responsible, during our lifetime, to keep it fresh and relevant?

And if so, how?

Ours is a young country. While inspired by circumstance and reflecting the best hope of an enlightened aristocracy, the Constitution was (and is) a flawed document. Without continual pruning and fertilizing, this democratic vine will wither away.

We firmly believe the Constitution only has legitimacy if re-ratified by each generation through the process of civic engagement and amendment. The time is ripe for the public to expand the Bill of Rights.

Our purpose here is to justify this perspective, identify areas for improvement, and then argue for a crowd-sourced, National Citizen’s Congress as the best pathway forward to maintain our democracy for centuries to come.

There are three parts to this argument. First, why obey the strictures of a 230 year old document? Patriotism, and obedience to the rule of law, are insufficient justifications. Second, under the well-known legal dictum “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” exactly what needs fixing? And third, who should take primary responsibility for the constitutions’ renewal?

Original Sinism:

There is one school of Constitutional interpretation known loosely as “originalism”. Rather than imposing modern sensibilities on the law (risking charges of judicial activism), it digs back into the historical record for guidance. Adherents then construe the law according to its “original meaning”. If that original meaning no longer fits the times and results in miscarriages of justice, one asks the legislature to revise statute- it’s not up to a judge to “make law”.

The idea is facially attractive and seductively neutral.

But there are three problems with originalism, each more damaging than the next. First, the Founding Fathers never agreed among themselves on the Constitution’s meaning. The document was a compromise, written under extraordinary time and political pressure.

The language was often intentionally left ambiguous to drive consensus. During Virginia’s ratification debate Richard Henry Lee complained to Patrick Henry² “the English language has been carefully culled to find words feeble in their Nature or doubtful in their meaning.” In the very first Congress after ratification, while debating the constitutionality of a national bank, Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton crossed swords over the exact meaning of the “necessary and proper” clause.

And they were both Founding Fathers! How can we, 200 years later, expect to know more about original intent than politicians who were there³ at the founding?

Second, in a stunning gesture of political inclusiveness, Congress allowed the people to ratify the Constitution, not the Founding Fathers. Thus, the people’s interpretation of its words must trump those of authorship. Otherwise, why ask for their assent? But from a modern vantage point, their views are unknown and unknowable. Along with a definitive assessment of original meaning.

Finally, the entire originalism debate is pointless. One side drags out an early diary and a couple of Federalist papers to prove the Second amendment applies to individual gun owners. The other side wields two early state constitutions and a ream of newspaper articles to prove the opposite. We learn more about the rhetorical cleverness and hidden agendas of its interpreters, than gain illumination of its original meaning.

We wave the flag of Originalism as an excuse to avoid productive debate and compromise.

As Louis Michael Seidman⁴ in his book “On Constitutional Disobedience” notes:

The upshot is that both progressives and conservatives are content to beat each other around the head and shoulders with charges of constitutional infidelity. …. Rather than insisting on tendentious interpretations of the Constitution designed to force the defeat of our adversaries, we ought to talk about the merits of their proposals and ours.

We will never agree on the scope of Second Amendment gun rights by pointing law review articles at each other in court. Instead, the citizens of this moment should debate the issue on its merits and negotiate a fresh interpretation. If no consensus emerges on constitutionally bound laws, then all three branches must avoid extreme constructions⁵. True, times change, and we may find it necessary to revisit this compact every fifty years- so be it. Better to amend frequently than let arcane debate contort our democracy.

Constitutional Legitimacy:

So why do we obey the Constitution if the words lack precise meaning? In fact, why pay attention to Constitution at all?

No one is bound to any legal contract unless that agreement is freely endorsed. As the Declaration of Independence promises, “just powers” arise from the “consent of the governed”. Yet our Constitution was never ratified by the very people it claimed to represent. Less than 15% of the colonists voted for its adoption⁶. The rest either objected to its terms, or as slaves or women did not qualify to vote. In fact, many states ratified for pragmatic reasons⁷- more acquiescence than full-throated endorsement of its democratic core principles.

Yet they were all bound by its terms.

None of us alive today participated in colonial deliberations or ratification.

Yet we all remain bound by its terms.

As Justice John Paul Stevens wrote⁸:

In his lecture “The Path of the Law,” printed in the Harvard Law Review in 1898, Oliver Wendell Holmes made this oft-quoted observation: “It is revolting to have no better reason for a rule of law than that it was so laid down in the time of Henry IV. It is still more revolting if the grounds upon which it was laid down have vanished long since and the rule simply persists from blind imitation of the past.”

Or as Thomas Jefferson famously argued⁹:

“On similar ground it may be proved that no society can make a perpetual constitution, or even a perpetual law. The earth belongs always to the living generation.”

Still, our laws are not immutable. We freely elect representatives who modify our statutes, refreshing them to meet the challenges of the present. We discover wiggle room in the “necessary and proper clause” or stretch the commerce clause far beyond its original scope to expand the reach of the federal government. Over the decades, courts reinterpret our founding documents with modern eyes, wielding its brevity and inconsistency as a cudgel to justify entirely new meanings.

We accept the rule of law, because we are complicit in its renewal.

But is this a “living” or a “zombie” Constitution? The unjustified veneration of the past as superior to the present often blocks consensus transformation. Compared¹⁰ to other nations (or even state constitutions¹¹), amendment is rare and episodic. There is no direct path for citizen initiatives¹². Law is (un)made by jurists and legislators who poorly reflect our country’s demographics and are out-of-step with their views.

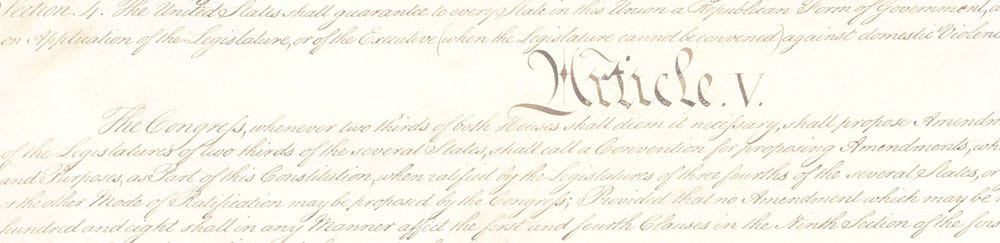

Yet it’s easy to take for granted the inherent brilliance of the Article V amendment process.

Prior to its incorporation in our Constitution, a coup or revolution was the only recourse when the governed, and the govern, fell out of sync. But with this new innovation, peaceful transition was possible.

Exactly this argument was made during ratification¹³:

… supporters of the Constitution discovered a weapon that would prove extremely valuable in nearly every battle yet to be fought over ratification. By holding out the prospect of amendments, the federalists found that they could allay fears and win over the undecided. Instead of having to convince skeptics of the absolute superiority of every aspect of their solution to the problems of U.S. government, they merely had to make a strong case for their central principles, argue persuasively that a workable method existed for repairing defects, and exhibit a willingness to consider immediate amendments. In the process, they presented an appealing image of the Constitution as genuinely republican, responsive to popular concerns, and flexible in adjusting the terms of government.

“Peaceful” is a relative term. The original sin of slavery, permeating the Constitution and our legal infrastructure to this day, took a bloody civil war to abolish. Street protests and near revolution during the 1960’s were ameliorated by granting 18 year-olds the vote. But we have never suffered a palace coup (though Jan 6th came close), the military remains apolitical, and the country smoothly transitioned after assassinations, premature deaths and two world wars.

The amendment process is the unsung hero of our democracy. Without amendments, such as the Bill of Rights, the colonies would never have coalesced into a singular nation. And, without the Bill of Rights and a handful of later amendments, the distinctly American mythos of rugged individualism that so marks our nation’s psyche, and is our one true religion, would never have emerged.

But what needs amending?

A flawed document

The Constitution is a work of man. By any objective standard- longevity, influence and tacit obedience- a remarkably successful one at that. All the more noteworthy given its many flaws.

These flaws take three forms- errors of omission, commission and indecision. In the absence of a robust amendment process, society has improvised numerous coping mechanisms¹⁴ to mute these three errors. Some are robust, others dangerously fragile. A complete inventory of flaws and unratified coping mechanisms exceeds this paper’s charter. Here, we simply provide two or three examples per category as motivation:

Errors of omission include inadvertent lapses, such as the initial lack of a vice-presidential succession plan. As well as significant flaws. The constitution contains no affirmative right to vote, a perplexing oversight in a democracy. The reason is simple- extending the franchise more broadly would have led to an immediate breakdown of the colonial aristocratic power structure. The Founding Fathers understood voting was a fundamental right, so invented every possible philosophical excuse to omit and blunt a general enfranchisement which could destabilizing the “natural order”. Or, in their vision, lead to “mob rule”.

We venerate our Founding Fathers and have fallen for this self-interested, oft-repeated justification that “voting is a privilege”. No degree of extra-constitutional coping mechanisms can fully atone for its impact, and we continue to fight for universal suffrage as a result.

The founders, naively in retrospect, failed to anticipate the almost immediate rise of the two-party system. With near-fatal consequences for democracy¹⁵. We comprehend this flaw during impeachment trials- where the senate loyally votes with their party’s president, rather than executing their constitutional oath to impartially judge. We see it reflected in legislative gridlock. In the dictatorial powers of party leaders suppressing bipartisan bills. In gerrymandering. In politicized senatorial “advise and consent”. And in the further polarization of the Supreme Court.

One can only speculate how the Founding Fathers might have rewound the democratic clockwork had they foreseen entrenched party politics.

Errors of commission must begin with the original sin of slavery. True, there would be no United States without incorporating some form slavery- that compromise was inevitable. But once slavery was forbidden, the consequences of slavery persisted. Despite three Reconstruction Era amendments and numerous civil rights bills, this shameful legacy is too deeply engrained in law and culture to erase without wholesale change.

The 13th amendment’s slavery exception for punishment of a crime (its wording cut and pasted from the Northwest Ordinance of 1787), opened the flood gates to disenfranchisement and de facto re-enslavement by criminalizing even trivial infractions. An exception which still festers in our high incarceration rates and felon disenfranchisement.

The Founding Fathers believed in MAD, Mutually Assured Destruction, long before the atomic era. They included very few proportionate¹⁶ mechanisms in the constitution to mediate between the three branches- it’s as if the only penalty available for shoplifting is the electric chair. Instead, each branch threatens the other with total war. Absent compromise, executive power was to be reined in by the legislature denying funds through the power of the purse. Or via the harsh penalty of impeachment. The President was granted nearly unlimited pardon powers to protect against a judiciary bent on intimidation by sentencing his colleagues. Like MAD, these remedies are often viewed as worse than the disease and are rarely employed. Allowing the President to deflect reasonable subpoenas from Congress, or to pardon his criminal co-conspirators. The judiciary unilaterally rules laws are unconstitutional on thin and inconsistent grounds, with little recourse other than packing the courts or denying jurisdiction.

And we are surprised when faith¹⁷ in democracy has waned…

Errors of indecision are either intentional or inadvertent. At under 7500 words (amended), each word in the constitution carries a heavy burden. Often the lack of detail was a negotiating tactic. Allowing disparate parties to “agree to disagree” in order to discover compromise.

Yet history demonstrates brevity is not always a virtue. “Agreeing to disagree” simply kicks the can down the road. These briefly worded articles and amendments often misfire exactly in the way critics at the time anticipated¹⁸, driving the constitution in unintended directions.

The Ninth Amendment’s “The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”, potentially the most important safeguard of individual privileges in the Bill of Rights, is basically moribund, partly because it provided so little specific guidance as to what those rights encompass¹⁹. Similarly, what is an “establishment” of religion? Which amendments are binding on the states? And so on.

Brevity undermines a key precept of any legal system- consistency and predictability. The silence of indecision often echoes for centuries.

Indecision damages our system of checks and balances. Article III outlines, at best, a slender vision for the judicial branch. The convention ran out of time, and patience, then expected the first Congress to fill in the blanks with an enabling judiciary statute. Contrary to popular opinion, under Article III the Supreme Court is not the final referee settling constitutional arguments between the President and Congress. Instead, each branch is entitled to its own interpretation²⁰ of the Constitution (MAD again). A brief Article III strands the court as a weak branch, beholden to the other two whenever they rewrite its rules and conditions for political gain.

Of course, brevity might turn out to be a “feature, not a flaw”. More detailed language is less flexible and adaptable. As Erwin Chemerinsky²¹ notes

“There is no doubt that this open-textured language is what has allowed the Constitution to survive for over 200 years and to govern a world radically different from the one that existed when it was drafted.”

But, in the absence of clarity, people’s intentions remain subjugated for decades as the Constitution’s mumbled words await clearer diction from later generations. “Indeed, most of the Bill of Rights provisions concerning criminal procedure were not incorporated until the Warren Court decisions of the 1960s.”²² “Brevity” should not delay justice for over a century…

Thus, we perceive the Constitution as a brilliant, but flawed document where unwritten traditions compensate for its deficiencies. Its distributed power structure tempers the madness of the mob, but with a heavy hand, suppressing innovation and openness to timely change.

Imagine a democratic habit where problems are not swept under the rug for decades. Where its citizens once again felt the law responded to their views during their lifetime. Where all parties took ownership to keep our democracy.

Who should modernize the Constitution?

Our democratic system is protected by three overlapping systems of checks and balances. At any single point in history, one or two of these protective walls are breached, but the remainder knits the bastion of democracy together.

First, there is the separation of powers between the Legislative, Executive and Judicial branches. Imperfect, mercurial and often abrogated by one branch. But in the main, it works as envisioned by the Founding Fathers. Unfortunately, this route to modernization is tempered by party politics, demographic misalignment, and structural impediments. Change from within is slow and unresponsive.

Second, there is the Federal system, distributing governmental power between the States and Washington. Fifty-one different viewpoints (DC included) bring diversity and innovation to our democratic experiment. For example, many states unilaterally granted voting rights to women²³ before 1920, forcing Congress to eventually act. It also, less positively, permitted Jim Crow to fester for over a century. Sometimes, state courts are bastions of progressive rulings, other times, the Supreme Court remaps the constitutional atlas. The Federal system is a slow and variable force of modernization.

Finally, there are the people, for whom the Constitution is designed to serve. Historically, almost all constitutional change can be traced back to civic engagement²⁴. The people choose their leaders through the power of the ballot. They compel states to amend their constitutions via public initiatives²⁵. They can, and do, agitate in the streets to promote new social norms, which eventually are incorporated in settled legal precedent. They overrule laws, for good or bad, by means of jury nullification. And they are entitled to certain inalienable rights, privileges and immunities which supersede legislative oversight.

Ultimately, the people are in charge. We all recognize people can be swayed by demagoguery, bad information and peer pressure. Crowds often make poor decisions they later regret. Which is why we accept the rule of law as a governor over our emotions.

But our current system of constitutional re-alignment is failing. The American people agree on numerous issues (>60%)²⁶ yet legislation fails to reflect societal change in a timely manner. Vested interests and partisan politics block amendments in Congress. The Article V convention path is long and convoluted. Moreover, the Founding Fathers neglected to specify binding rules for such a convention, leaving open the possibility it might spin out of control, radically and suddenly reframing our entire way of life. More troubling, we have convinced ourselves these impediments are a wise brake on mob rule. Allowing injustice to fester for decades because constitutional change is frowned upon.²⁷

We must bring the government and people closer together²⁸, or risk losing their trust entirely.

A National Citizen’s Convention

How will we accomplish this goal? By respecting the Article V Constitutional Convention’s “spirit” while sidestepping the petition route. Instead of asking for permission from state legislatures, we will hold a “National Citizen’s Convention” to debate, prioritize and then help ratify a new Bill of Rights. We will leverage the energy and wisdom of the crowd to avoid phrasing amendments with unclear language. And we will harness social media and public protest to build a groundswell of supporters to pressure Congress into acting, and the states into ratifying.

More details on the National Citizen’s Convention here.

TL:DR References and supporting material

[1] https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/12/18/republic-if-you-can-keep-it-did-ben-franklin-really-sayimpeachment-days-favorite-quote/ [2] Richard Henry Lee and William Grayson to the speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates, September 28, 1789, in Veit, Bowling, and Bickford, eds., Creating the Bill of Rights, p 299. [3] And if 12 founders agree with one position, while 14 disagree, do we apply majority rule? Or weight the outcome by the founder’s fame and erudition? [4] Seidman, Louis Michael. On Constitutional Disobedience (Inalienable Rights). Oxford University Press (2012). Introduction. [5] This is essentially the strategy of the Robert’s Court on gun control rights. [6] var sources, including The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States by Alexander Keyssar and America’s Constitution: A Biography by Amar, Akhil Reed. 5% is claimed by Max Lerner in Constitution and Court as Symbols, 46 Yale L.J. 1290, 1296 (1937). In a remarkable loosening of voting qualifications away from traditional property requirements, almost all state constitutional ratifying conventions temporarily expanded the franchise to freemen. Even so, the votes were close, and ratification just squeaked through. [7] “Delaware, convinced that under the new federal government its debt burden would be relieved by a stronger currency and its share of taxation would be reduced as a result of import duties and sales of western lands, was most eager to endorse the instrument…. Many Connecticut delegates, like those in Delaware, New Jersey, and Georgia who had already acted, concluded that their states had little choice but to embrace the new Constitution….” Kyvig, David E.. Explicit and Authentic Acts. University Press of Kansas, 2016 Chapter 4. [8] Six Amendments: How and Why We Should Change the Constitution by John Paul Stevens. [9] Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, Volume 15: 27 March 1789 to 30 November 1789 (Princeton University Press, 1958), 392–8 https://jeffersonpapers.princeton.edu/selected-documents/thomas-jefferson-james-madison [10] “The amendment process spelled out in Article V of the Constitution is exceedingly cumbersome. Indeed, the American Constitution is more difficult to amend than any other national constitution in the world.” Seidman, Louis Michael. On Constitutional Disobedience (Inalienable Rights) Chapt. 2, Oxford University Press (2012). [11] The Maryland State Constitutions Project reported in 2000 that “there have been almost 150 state constitutions, they have been amended roughly 12,000 times, and the text of the constitutions and their amendments comprises about 15,000 pages of text.” http://www.stateconstitutions.umd.edu/index.aspx Data analyzed from https://ballotpedia.org/Amending_state_constitutions and http://www.iandrinstitute.org [12] Some 24 states permit citizen initiatives. Eighteen allow citizens to propose constitutional amendments. http://www.iandrinstitute.org/states.cfm [13] Kyvig, David E.. Explicit and Authentic Acts. University Press of Kansas. 2016 Chapter 4. [14] For example, independent agencies and independent counsels provide a check on unitary executive power, addressing the constitutional flaw of asking the executive to be both judge and jury in its own malfeasance. The Supreme Court created an entirely synthetic set of rules around “justiciability” which allows it to sit on the sidelines when they deem an issue to be “political”. Conversely, their temporal decisions are “constitutionalized” into fixed black-letter law. Emasculating one of the three checks and balances. And disenfranchising the public. [15] John Adams to Jonathan Jackson, 2 October 1780 “There is nothing I dread So much, as a Division of the Republick into two great Parties, each arranged under its Leader, and concerting Measures in opposition to each other. This, in my humble Apprehension is to be dreaded as the greatest political Evil, under our Constitution.” https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-10-02-0113 [16] There are a few. For example, “Advise and consent” on nominations, presidential vetoes, immunity and judicial review are somewhat proportional checks and balance. [17] Public trust in the government remains near historic lows. Only 17% of Americans today say they can trust the government in Washington to do what is right “just about always” (3%) or “most of the time” (14%). https://www.people-press.org/2019/04/11/public-trust-in-government-1958-2019/ . Dissatisfaction with democracy has risen worldwide https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/02/27/democratic-rights-popular-globally-butcommitment-to-them-not-always-strong/ [18] “Although the Eleventh Amendment is over 200 years old, there still is no agreement as to what it means or what it prohibits.” Chemerinsky, Erwin. Aspen Student Treatise for Constitutional Law: Principles and Policies (Aspen Student Treatise Series) (p. 194). Wolters Kluwer Law & Business. Kindle Edition. [19] It was original thought enumerating inalienable rights risked limiting rights to only that list. Silence was intended to signal the list was expansive. History demonstrates exactly the opposite occurred. [20] “Broadly speaking, the Constitution enabled and in some cases obliged each of the three main departments — indeed, each half of the legislature and perhaps each half of the judiciary — to thwart schemes that it, and it alone, deemed unconstitutional.” p. 60; “Accustomed as we are to seeing the judiciary — particularly, the Supreme Court — as the sole custodian and unique interpreter of the Constitution, many modern Americans might bridle at the idea that the framers envisioned the president as America’s first magistrate, with important and independent authority to construe and defend the Constitution” Amar, Akhil Reed. America’s Constitution: A Biography (p. 179). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.; “Interestingly, Article III never expressly grants the federal courts the power to review the constitutionality of federal or state laws or executive actions.” Chemerinsky, Erwin. Aspen Student Treatise for Constitutional Law: Principles and Policies (Aspen Student Treatise Series) (p. 35). Wolters Kluwer Law & Business. Kindle Edition. [21] Ibid Chemerinsky (pp. 16–17). [22] Ibid Chemerinsky (p 530). [23] “By the time the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution was ratified in 1920, guaranteeing women the right to vote, fifteen states had already granted women the right to vote generally, and another twelve had granted them the right to vote for president.” Cole, David. Engines of Liberty (p. 31). Basic Books. Kindle Edition. [24] “How Social Movements Change (or Fail to Change) the Constitution: The Case of the New Departure,” Suffolk Law Review 39 (2005): 27; Jack Balkin ; Engines of Liberty , Cole, David., Basic Books 2017. [25] Notably, creating independent redistricting commissions, enfranchising felons, tightening on-line privacy, .. [26] For example, on reasonable gun control https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/08/30/where-the-publicstands-on-key-issues-that-could-come-before-the-supreme-court/and equal rights for women, along with strong protections for free speech https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2015/11/18/global-support-for-principle-of-freeexpression-but-opposition-to-some-forms-of-speech/ and eliminating the electoral college https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/abolishing-the-electoral-college-used-to-be-bipartisan-position-not-anymore/ [27] Taylor, Steven L.. A Different Democracy: American Government in a 31-Country Perspective . Yale University Press. 2014 Even a casual examination of other democratic demonstrates American exceptionalism has fallen behind the times and is out of sync with the public. Our democracy is no longer a shining beacon of inspiration for the world. [28] https://www.pewresearch.org/pp_2019-12-16_political-values_01-02/